Artist statement:

Faith—whether religious or ideological—is an act of submission: not to truth alone, but often to comfort. Holy Communion explores this tension by replacing bread and wine with water and blue pills, referencing The Matrix. The ritual becomes a site of inquiry—does belief emerge from conviction, or from convenience?

The performance isolates one participant in a VR environment, while the audience remains outside, observing through fragmented projections across three vertical gauze screens. This setup echoes Plato’s Cave—where reality is mediated, inherited, and reframed. The participant, immersed in an ornate cathedral-like VR space, encounters traditional communion elements: real bread and wine. Meanwhile, the audience sees a minimalist, white lab—ritual stripped of mystery and exposed to light.

By juxtaposing these spaces, Holy Communion asks whether faith is shaped more by what we see collectively or by the internal, immersive narratives we accept alone. The work doesn't dismantle faith, but reveals its scaffolding: the repetition, the symbolism, and the quiet tension between submission and awareness.

Context & intention:

Fast forward to 2020, when the pandemic moved all physical gatherings online—even sacred rituals like Holy Communion. Suddenly, people were performing it at home, with their own bread and wine, through a screen. That shift—blending 2000 years of tradition with digital convenience—made me pause. It felt strange, and yet revealing.

It made me ask: why do we perform these rituals in such specific ways? Are they truly acts of faithfulness, or are we just following patterns that feel sacred because they’re old? To what extent are these habits rooted in spiritual depth, and when do they become rigid, even closed-minded?

There are people who insist you must never stop going to church, never miss a gathering—as if that’s the definition of faith. But often, these expectations aren’t even from scripture. They just sound biblically correct. When the communion ritual moved online, something felt off. Not because the form changed, but because it revealed how much of it had become automatic. Less about belief, more about routine. Less genuine.

And that change didn’t go away. Online church stayed. It’s now a normalized form of worship—and that continuity raises even more questions about how faith adapts, or fails to adapt, in the digital age.

This work was also created with a specific audience in mind—some of whom, including my TA, weren’t present to experience the performance in person. That absence directly shaped how I approached the piece. Holy Communion needed to be more than just a live moment; it had to live on through its documentation, and speak clearly to viewers who would only encounter it later. That became part of the challenge: to make something intimate, reflective, and layered, but still accessible to those outside the room.

It has been said many times: we make a world, and in that world, the world makes us. This is our condition—we are embedded in and shaped by our context. This work is my way of exploring how we make meaning through ritual, repetition, and belief. It's not just about tradition—it’s about self-awareness. How well do we understand why we do what we do? How often do we examine the stories we’ve inherited, or the truths we quietly obey?

Holy Communion isn’t about criticizing faith. It’s about asking whether we are truly "woke" inside it.

Moodboard & Concepts

Projections, Vr & AR

In Holy Communion, projections operate both literally and metaphorically. Visually, the vertical screens form a digital cave—referencing Plato’s Allegory of the Cave—where shadows and illusions define reality. These curated visuals immerse the audience in a world shaped by filtered truths, fragmented media, and performative identities. In this space, what is seen is not necessarily what is real, echoing our condition in the post-truth age: where projections of truth—not truth itself—are consumed, shared, and believed.

Metaphorically, the projections reflect how ideologies, faith systems, and personal convictions are socially projected. What we believe is often shaped less by internal reflection and more by the expectations and appearances of others. The audience is placed in a system where belief and performance blur, prompting the question: What if everything I believe is someone else’s projection?

Both VR and AR are used in separate versions of the performance as a continuation of this exploration of perception. They function not just as tools, but as conceptual layers that challenge reality itself. Inspired by Plato’s Cave, the work questions whether what we experience is truth—or just perception.

In the first version, VR is used to project a fully immersive sacred environment into a single participant. Wearing a headset, they appear in elaborate ceremonial attire, placed inside a richly detailed, cathedral-like space filled with iconographic meaning. This immersive world replaces their physical surroundings entirely, isolating them from the rest of the audience.

In the second version, AR (Augmented Reality) is accessed through phones, layering digital religious imagery over the real space in real time. Unlike VR, AR is shared and visible to all—less immersive, more ambient. It mirrors our everyday interaction with screens, where fragments of constructed meaning hover over reality.

These technologies are not just visual effects. They symbolize how people receive information in a mediated world and offer the audience a way to observe what it looks like when someone makes a faith decision within such a space. Whether immersive or layered, both VR and AR ask: When reality is constructed for you, how do you know what to believe?

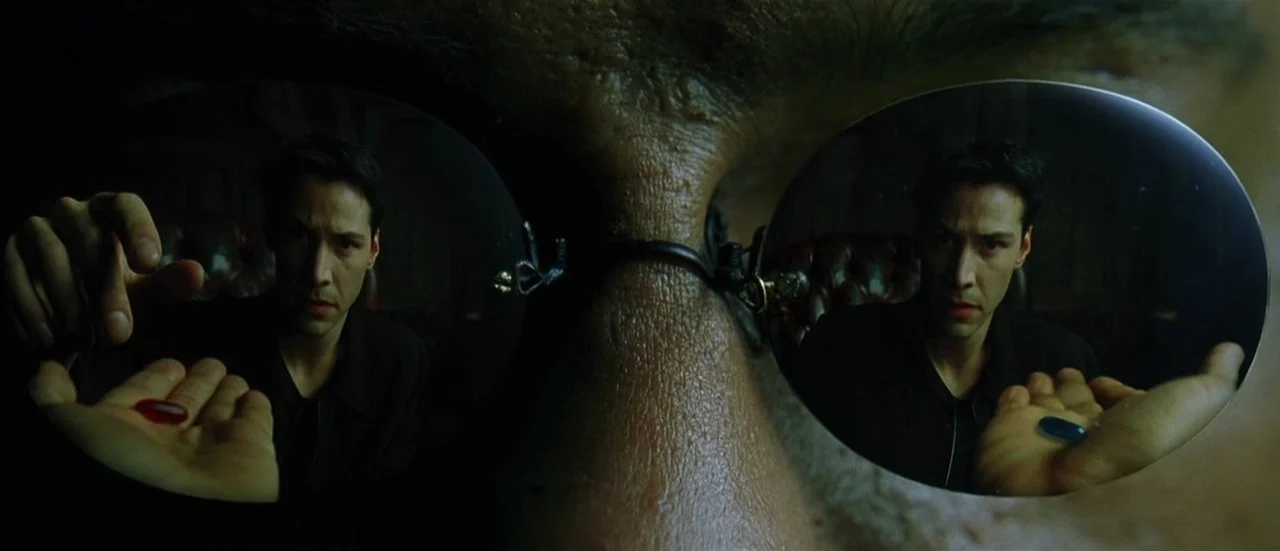

Blue pills

The blue pill is a familiar cultural artifact—instantly recognizable, loaded with meaning. In The Matrix, it represents the choice to remain comfortable and unquestioning. In Holy Communion, however, it serves a different role: not to numb, but to disturb.

In this context, the pill interrupts ritual. In many Christian traditions, communion is a deeply symbolic act—affirming belief in Jesus’s death, resurrection, and return. Yet over time, the gesture can become automatic, its meaning dulled by repetition. By replacing bread and wine with a blue pill and water, the performance reframes communion as something unfamiliar, even clinical. It disrupts familiarity. It creates hesitation.

And that hesitation is intentional. The moment before swallowing—when the participant quietly asks, What is this? Why am I taking it?—is the core of the work. The pill offers no clarity, only space for awareness.

This act draws a quiet parallel to the Death of Socrates. Like Socrates willingly drinking hemlock, the participant ingests something whose meaning is uncertain—but symbolically significant. For Socrates, the act was not about submission to law or punishment, but a willingness to bypass them entirely in order to stay true to his principles. He accepted death not out of obedience, but as a final act of philosophical clarity.

In Holy Communion, the stakes are not life or death—but the question of submission still holds weight. Would you participate in a ritual just because it’s expected of you? Would you take something simply because it was offered? Or would you pause—like Socrates—and make the act your own, with full awareness of its meaning, or its absence?

This isn’t a rejection of faith. It’s an invitation to look closer. To ask whether belief is active or inherited. To consider whether ritual affirms conviction—or conceals the lack of it. The pill doesn’t answer these questions. It simply makes them unavoidable.

minimalist set & costume

The performance unfolds within a minimal, sterile environment—a white, cube-like room intentionally devoid of traditional Christian architecture, ornamentation, and atmosphere. There are no stained glass windows, no altars, no symbols of sanctity—just bare white walls, clean lines, and clinical lighting.

This deliberate choice isolates the ritual from familiar visual cues of faith, allowing the gestures and choices of the participants to stand on their own. Without the comfort of tradition or the weight of sacred architecture, the audience is presented with a blank canvas—a space where belief cannot hide behind aesthetics.

The whiteness of the room evokes multiple associations: a laboratory, a medical facility, a testing ground. It shifts the ritual from sacred to sterile, and in doing so, asks whether the power of communion lies in the act itself—or in the setting that frames it.

The space doesn’t reject faith, but it removes its costume. What happens to belief when all signs of holiness are stripped away? What remains when tradition is reduced to its most basic gestures?

Technical process

Sharktooth Scrim

To create the ghostly, semi-transparent effect of the screens, I used sharktooth gauze—a type of theatrical scrim—framed vertically, with short-throw projectors placed directly beneath each frame. Sharktooth gauze is traditionally used in dark, tightly controlled lighting environments, where its transparency allows it to disappear entirely under the right conditions. In theatre, it often supports illusion—used to conceal and reveal, to create magic and mystery for the audience.

In Holy Communion, I deliberately subverted that convention. Rather than hiding the technique and keeping the audience in the dark, I wanted to expose it. The gauze remains clearly visible—its mesh and texture catching ambient light, never fully disappearing. The audience doesn’t just see the projection; they see the screen, the frame, the apparatus that holds it all together. The setup is built for scrutiny, not illusion.

projected performer frames

This design choice is inseparable from the work’s conceptual aim. The minimalist set is not an aesthetic decision alone—it creates space for dissection. The ritual is not being dismantled, but made transparent. By revealing the mechanism behind the gesture, the performance invites the audience to consider how belief is structured, repeated, and mediated. The sharktooth gauze, in this context, becomes more than a screen—it becomes a metaphor for inherited systems: porous, visible, open to interpretation, yet still capable of carrying meaning.

Faith here isn’t destroyed by visibility—it’s confronted. Ritual doesn’t lose its power when laid bare; it becomes something we can actually examine. In the same way that the performers pass gestures across fragmented screens, the piece passes on belief—not as a finished truth, but as a structure exposed to light, context, and choice.

Projection Mapping

Video feed (left) & projection mapping (right)

This screenshot captures the projection mapping process in Isadora, where a single continuous video feed is seamlessly split across three physical frames. On the left is the original video source, featuring all three performers within one composite shot. On the right is the projection output, where that single image is mapped onto three separate rectangular zones—each aligned with a gauze screen in the physical installation.

Though the installation appears to present three isolated figures, these are not separate videos. Instead, they are carefully sliced segments of the same video, mapped to maintain the illusion of interaction across the screens. The performers' gestures—such as passing the bread and wine—move fluidly from one frame to the next, traversing the physical gaps between them. This continuity reinforces one of the central ideas of the work: that faith, like image, is transmitted through fragmented frames—shaped by the structure that carries it.

What results is not only a spatial illusion, but a projected reality: one that appears whole, yet is composed of selective framing and curated visibility. The projection mapping becomes a metaphor for how meaning, belief, and ritual are mediated—passed down through constructed forms that often appear seamless, but are stitched together across context and omission. The visible cracks—the borders between screens—echo the conceptual gaps in inherited faith: where something is always lost, even as something powerful is passed on.

lighting design

The lighting for Holy Communion was designed to resemble a single beam piercing into a cave-like space, referencing Plato’s Allegory of the Cave. As shown above, the light falls precisely on the participant's ritual zone, echoing a moment of revelation or clarity entering darkness.

There are two images on the right. The top one is a rendered side view based on the floor plan of Whitelabs, showing how the light is planned to hit the set, using the actual railing arrangement for all controllable lights. The image below it is a photo taken during the work-in-progress phase, capturing how the light behaves on the physical set when it hits the gauze and pedestal.

This focused beam is both functional and symbolic. It isolates the participant in a narrow corridor of light, suggesting the rare, individual nature of awareness—while the rest of the space remains in shadow. The rest of the audience quietly observe and witness, perhaps even judge or form critical thoughts—much like the figures in Plato’s cave, watching shadows and drawing conclusions from partial truths.

Rather than flooding the space, the light draws a boundary. It does not illuminate everything—it illuminates a choice.

Execution & work in progress

Captured from work in progress

The hands before us have left their mark,

a shape traced in dust, a pattern we follow.

Is it the hunger for truth that calls us here?

Or the residue of practiced faith that came before?

In performance, this mapped illusion unfolds as a ritual in motion: the bread and wine move from screen to screen, hand to hand, seemingly uninterrupted. Yet the spaces between—the negative space, the borders, the quiet voids—become charged with meaning. These gaps are not just technical, but conceptual. They represent the distance between intention and reception, between tradition and interpretation. The performers’ gestures flow across frames, but what’s carried through is never entirely whole.

The act of passing through mediated surfaces reflects how inherited faith is transmitted—ritualized and repeated, but refracted through the conditions of its time. The screen does not simply display; it edits, fragments, and frames. What we receive has already been shaped. In this way, the projections become a reflection of belief itself: visible, moving, continuous, yet always partially obscured by the medium through which it travels.

Later in the performance, these ideas are echoed in lines of projected text: "The hands before us have left their mark, a shape traced in dust, a pattern we follow." and "Is it the hunger for truth that calls us here? Or the residue of practiced faith that came before?" These phrases arrive after the ritual has already been enacted, not to explain it, but to reflect on its afterimage—what lingers, what slips away, and what gets silently carried forward.

Captured VR/ar View vs rendered live set

The video on the left shows what the volunteer sees inside the VR headset, while the image on the right presents a rendered top-down view of the physical installation. Together, they reveal the layered duality at the heart of the performance.

In the rendered image, we see the interactive volunteer standing in front of the central pedestal, wearing a VR headset, surrounded by three vertical projection screens. From the audience’s perspective, this setup is minimal, clean, and fully exposed. The screens display a single continuous video, mapped seamlessly across three gauze surfaces. The physical space makes no attempt to hide its construction—the mechanics are visible, the symbolism dissected.

In contrast, the VR video reveals the participant’s experience from within: a mirrored world of the same communion table, now set within an ornate, cathedral-like interior. The three performers, who appear as projections in the real space, now surround the table as embodied presences. The ritual itself also changes—inside VR, the symbolic elements revert from blue pills and water to traditional bread and wine, restoring the ceremony to its familiar, sacred form.

This contrast—between what the audience sees and what the volunteer experiences—highlights the project’s central question: where does belief take root? In the transparent, deconstructed ritual we witness together? Or in the immersive, curated world we choose to enter alone?

Is belief a product of shared knowledge, or a conviction shaped by personal experience?

Does it arise from what we inherit and observe, or from what we assemble in the privacy of our own perception?

And when all the traditional elements are stripped away, does that clarity reaffirm the choices we've made—or begin to quietly challenge them?

Performance transcript:

Some say we live in a cave, watching only shadows on the wall.

Some say we are offered a choice—

One that will wake us, or keep us dreaming.

But before a choice, there is belief.

Before belief, a moment of surrender.

On the night he was betrayed, the son of man took bread, broke it, and said:

"This is my body, given for you. Do this in remembrance of me."

He lifted the cup and said:

"This is my blood, poured out for you. Do this in remembrance of me "

And so they ate, and so they drank.

And so they remembered.

Two thousand years have passed.

Still, we gather. Still, we receive.

The hands before us have left their mark,

a shape traced in dust, a pattern we follow.

Is it the hunger for truth that calls us here?

Or the residue of practiced faith that came before?

You may not know the story.

You may not know the meaning.

But even without knowing, you will make a choice.

If you are uncertain of what you are partaking in, you may let the tray pass.

To abstain is not to reject, just as to accept is not to understand.

There is no shame in uncertainty. But there is weight in every choice.

You may take this as it is given.

Or you may choose to watch, to wait, to wonder.

Or reinterpret, reimagine...

But when the choice is made, what follows?

Is it the act that changes you, or the knowing that you have acted?

You carry it now—whether in the body or in the mind. What remains is not what was given, but what cannot be forgotten.

And now, you have crossed a threshold.

Whether it leads anywhere, only time will tell.

A gesture made, and a moment passed.

What was ritual is now memory, and what was offered is now yours to bear.

Performance Glossary:

religious Awareness and ethics in Symbolic Practice

My decision to replace the traditional communion elements—bread and wine—with water and a blue pill was not made lightly. It was based on a theological and conceptual understanding of representation in Christian ritual. Communion, at its core, is a reenactment of the Last Supper. Whether one uses actual wine or grape juice, unleavened bread or biscuits, these are already representations of Christ’s body and blood. What we receive is not the literal flesh or blood of Jesus, but a symbolic act of remembrance, obedience, and reflection.

“For whenever you eat this bread and drink this cup, you proclaim the Lord’s death until he comes.”

— 1 Corinthians 11:26

In that sense, what I offered was a representation of a representation—a symbolic gesture designed to help us reflect on why we perform this ritual at all. The blue pill and water were never intended to desecrate the ritual, but to draw attention to its origin, meaning, and purpose, especially in an age where repetition often eclipses reflection.

“Whoever, therefore, eats the bread or drinks the cup of the Lord in an unworthy manner will be guilty concerning the body and blood of the Lord... For anyone who eats and drinks without discerning the body eats and drinks judgment on himself.”

— 1 Corinthians 11:27–29

The point is not in the physical material consumed, but in the awareness with which we partake. That awareness was the very subject of this work.

Representation also operates powerfully in another realm: medicine. The placebo effect is a psychological phenomenon where the belief in a pill’s effectiveness can produce real physiological change—even when the pill contains no active ingredients. The blue pill I used was 100% inert—an empty capsule. Yet, like communion, its power lies not in what it is, but in what it symbolizes.

I created Holy Communion with the belief that my work could open space for real conversations—not with those looking to be offended, but with honest believers willing to confront doubt, contradiction, and complexity. I trust in my ability to approach these themes with care, sincerity, and a desire to understand rather than provoke.

Having grown up in a Christian environment, I know how difficult it is to have these conversations—how rare it is to question faith openly without it being seen as disrespect. That experience shaped this piece. It was never about dismantling belief, but about making space to look at it clearly, and hoping for a conversation.

I’m also aware that religion is a protected characteristic in the UK. With that in mind, the work was designed to give viewers full agency—to participate, abstain, or simply observe—without judgment. The blue pill was never intended to shock, but to symbolize that choice.

This performance asked: If a symbol can still affect us—even when we know it’s symbolic—how deeply have we internalised the things we believe in? That’s not an attack on faith. It’s an invitation to examine it more honestly.

Reflection on health and safety

The most unexpected resistance I encountered came when I proposed a simple gesture: offering something entirely harmless, fully disclosed, and symbolically charged. The pill was empty, gelatin-based, and entirely inert. From a medical standpoint, there was no risk involved. But the proposal was initially turned down under health and safety guidelines. The concern wasn’t about the substance itself—it posed no real danger—but about the act of ingesting it. There was fear it might trigger psychological discomfort, confusion, or evoke the feeling of performing a medicated or ritual act.

And that hesitation, ironically, confirmed everything the work was trying to examine. The reaction wasn’t about external danger—it was about internal response. The anxiety came not from the object, but from the act of reenactment. It showed me that the power of ritual lives not in the materials, but in the mind—in how meaning is projected, internalised, and believed.

I believe that honest faith should arise within the individual—unfiltered, self-examined, and free from the pressure of external interference. But I also recognise that such clarity is difficult to hold onto. If we’re not careful, our personal convictions are shaped—often unconsciously—by the traditions, rituals, and aesthetics that surround us. Christianity has constructed layers of symbolic meaning over millennia. One has to wonder: what would it look like to approach faith without all the filters?

It’s been said many times—we make a world, and that world, in turn, makes us. This is our condition. We are embedded in and shaped by our contexts. With that awareness, I didn’t see Holy Communion as an act of criticism, but as an invitation—an attempt not only to dissect faith but, in some way, to serve it. To strip back the noise, the costumes, the architecture, and simply ask: what’s left? Not to destroy belief, but to give it the chance to speak plainly, to be questioned, and maybe even better understood.

This incident revealed just how easily belief, discomfort, or reverence can be triggered by representation alone—how performance and faith share a dependency on imagination and perception, more than on tangible form. While religious architecture, garments, and traditions help shape the experience of faith, their symbolic force ultimately relies on personal projection. What matters is not just what is seen, but what is felt.

CREDITS:

Performer 1 – Anna Cantes |

Performer 2 – Andrea Proano |

Performer 3 – Richard

Special thanks to Dimitrios Coumados, Michael Breakey, Michael Ste Croix, and Faust Peneyra for assisting with technological support and guidance.